Introducing my trauma-informed book about Lord Byron

Inspirations behind a historical fiction novel from a queer, disabled writer

[Content guidance: Trauma and traumatising events, sexual assault, child abuse by parents and carers, bullying, references to autistic meltdown/overwhelm.]

How does a trans journalist, and one who swore off ever writing fiction at that, end up writing a novel on Lord Byron?

Last year, on the 200th anniversary of Byron’s death, I visited Newstead Abbey—the poet’s ancestral home, and my most enduringly beloved childhood haunt.

A decade had passed, and a National Lottery Funding prize won for the house and grounds, since the last time I’d visited.

Despite the long stretch of time, the difference the money had made was immediately obvious and incredible.

Before, what rooms there were to explore inside the house had stood on their own, with little knowledge to embellish them unless you took the guided tour.

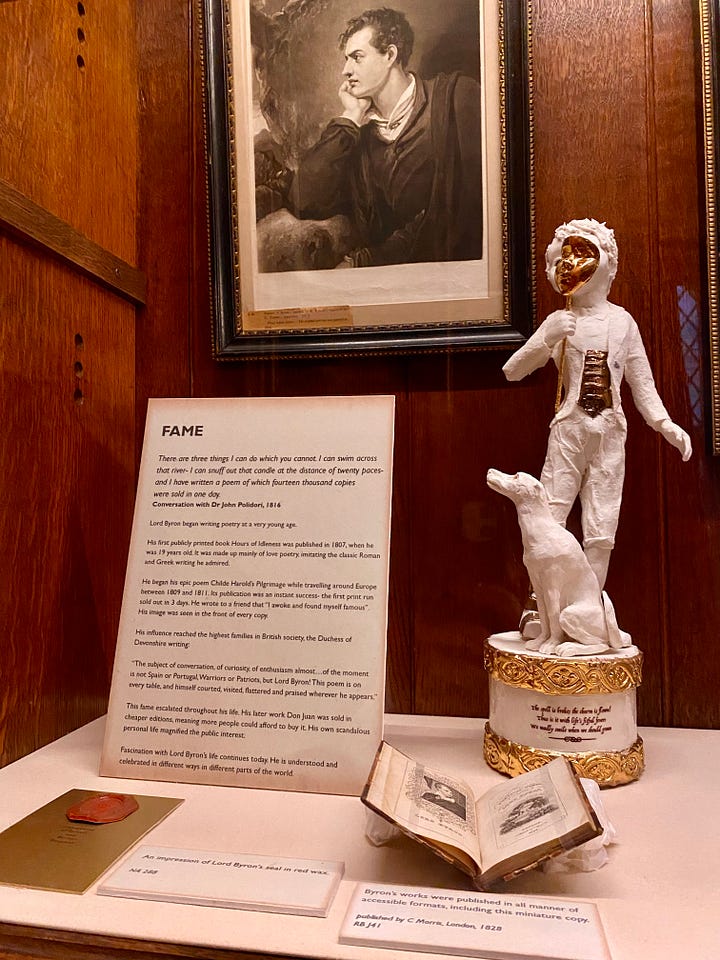

Now, there are walls of glorious glass fronted cabinets stuffed with the lord’s memorabilia and memento mori, letters, locks of hair, the poetic licence other creatives have taken with his iconic, mythologised image.

Byron has a gift shop. A gift shop! Full of books about him, mini print portraits of him and… fantastically hued ornamental peacocks. Because regular-coloured peacocks and peahens strut the garden, and Byron reputedly kept a few as pets for a time, after all.

Would his ego love it, or despise the commoditisation of his life and written legacy? We’ll never know.

But something came to me, as I saw the old place anew. When we’re discussing historical figures in an academic way, something uncomfortable can happen.

Just look at Byron. As I walked around his ancestral home, one placard would speak of his bisexuality, or the problematic-to-downright-abusive ways he expressed it. Another, his physical disability. One display opened up his grapples with mental illness. Another his fame, adoringly unruly rabble of fans, and cis-hetero sex symbol status as history’s first celebrity.

These aspects of him and his life are so often handled as separate things, each one almost as its own splinter personality. Not as mere parts informing the whole, the human who amassed and carried each of them through his short life.

When this compartmentalising is done, it also overlooks the inevitable trauma from being made of all these parts at once.

George Gordon Byron was bullied as a child—even by his mother—for his disabled body, his lisp, for being ‘queer’ (in the old sense that meant peculiar, strange, odd).

When he became a lord, he was teased for that too. Brought to tears in the classroom when his new name, first called out in attendance, caused the uproar inflicted by children—sometimes innocently, sometimes not—on other, singled-out children.

His sensitivity to attention and overstimulation, and anxieties over change, are just a couple of reasons I think he was autistic. (ADHD too, but I have enough Byronic neurodivergence receipts for that to be a whole other post.)

He was a survivor of multiple childhood sexual assaults, his nurse May Gray a repeat offender. This continued while Byron was left in her care for an extended period, as single mum Catherine Gordon needed to see to matters at the newly acquired, severely neglected Newstead estate.

These young experiences of his, though not exactly the same as mine, in many places bear more than a passing resemblance. Enough for me to feel a kinship with him that gets stickier for acknowledging his worst deeds.

The reality of the trauma that arises from living through and with such experiences is misunderstood or ignored by too many.

Too many historical and biographical writings overlook the role trauma must have played in Byron’s life—for good and for bad, mad, and dangerous.

That’s why I’m writing a trauma-informed, adult historical novel about his childhood. For now it has the working title ‘Child Byron’, in an almost unavoidable reference to Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, the narrative poem that made him famous in 1812.

I’ll explore and examine how developmental trauma and traumatic experiences informed his humanity.

And I’ll bring this in unison, as it should be, with his queerness (the strange and just plain gay). With the gender nonconformity, disability, mental illness, and neurodivergence, which all informed the person Byron was. At least, as far as I’m concerned.

Whew, that was a lot. How do I walk it back to end on a light and exciting note from here?

Because ultimately, that’s how I feel. I’m so excited to have this wonderful, important creative idea curled up, stirring awake, in the lap of my brain.

I’m thrilled to begin sharing the process with you, as I start in the planning and research stages.

And I hope, at the end of all this, by hook or by crook, we’ll have a book that’s still in places fun(?!) and enjoyable to read. (I know I want some dark academia, both in vibey aesthetics and shady school politics, during Byron’s Harrow years. And right now, I think those are going to form the lion’s share of the story.)

I hope, if you’re sticking around, that you can enjoy the process with me, along with any updates I have to share.

And if you have stuck around to the end of this little mission statement, thank you. As you’ve likely gathered, this project means a lot to me, for many reasons.

But it’ll mean much more when it eventually comes to you, my readers.

If you’re curious about anything to do with this book, your comments and questions are all too welcome. Meanwhile, if you want to follow along, I’d love to have you here.